The UK government spends a great deal on supporting dyslexic students in HE – and they almost certainly get value back on that money in the workplace. At the same time, many dyslexic students go unnoticed and struggle without specialist support. We have to get our dyslexic students through university in good fettle, smoothing their thoroughly frustrating path where we can.

‘If education pivoted around creativity or practical competencies or social skills or audio visual skills, you’d be setting up learner support units for non-dyslexic people,’ says technology consultant (and dyslexic) Alistair McNaught (2012). ‘It’s a cultural choice to link learning so tightly to reading and writing.’

Dyslexia often comes with very considerable strengths, as hugely successful banking organisations such as Goldman Sachs recognise when they give time concessions to dyslexic candidates in interviews. And at one time Harvard Business School was seeking out successful dyslexics to understand their skills as entrepreneurs and to develop those abilities in its own students.

However, dyslexia also comes with challenges that are produced by the emphasis on literacy skills in education. The combination of poor working memory and slow speed of processing information impact reading, writing and listening. Poor skills in processing sounds (phonological processing) and lack of automaticity in writing and reading deepen the frustration and difficulties.

Designing for dyslexia

The good news in supporting dyslexic students in HE – as under the Equality Act 2010 you are bound to do – is that the right adjustments can leverage benefits for more or less every student. Here are some of the do’s and possible dont’s:

Make it multisensory.

Include multiple ways for learners to engage with the content such as things to do, say, see and hear. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) may give you some useful ideas for doing this.

Make assessments inclusive at the point of design.

Giving students extra time highlights difference; extra time ‘others’ students (and I’ve heard very generous-spirited students cry ‘unfair, unfair’ when dyslexic students have extra time). Offer alternatives to the inevitable written assessments, which put pressure on dyslexics and international students – neither group is likely to demonstrate what they know, understand and can argue coherently without a huge struggle.

Keep everything simple.

Those long turgid unit handbooks do no one any favours and, as the great (dyslexic) Albert Einstein probably said, ‘Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.’ Keep the sentences short so that you do not put unnecessary pressure on the weakness in the dyslexic working memory – or, indeed, on the working memory capacity of all students. (In this connection, you may like to check out Sweller’s 1988 Cognitive Load Theory.) Stick to one idea per sentence – and avoid double negatives: these can really fox dyslexics, and probably a lot of other students as well. This may be the moment to test the controversial ChatGPT, which will simplify text while you blink.

Create handbooks and unit material in Word.

It is easy to customise text with Word and to convert this into programs that will read text to students. And see that all text (including slides) is, as far as possible, on an off-white (possibly grey or a pale pink) background. Some dyslexics have trouble with black/white contrast (known mainly now as visual stress) as do many other people – and whatever you do, resist the temptation to reverse out a light text onto a dark background. The British Dyslexia Association (BDA) Style Guide is very helpful on choosing fonts and layout as well as simplifying material (see below).

Avoid anything unnecessary or distracting in slides.

It’s easy to get carried away by free pictures on Google and fascinating (though tangential) facts and figures – Cognitive Load Theory again. Pretty your slides might be; but if they are in any way confusing, alas, they must go.

Reduce the number of lectures.

Where possible, avoid them – you can do so many other more inclusive and engaging activities online and in class. If you must lecture, make sure the slides are available beforehand, and break lectures up into manageable chunks.

Provide reading material in advance.

If you want students to discuss a passage of text in class, give them an opportunity to read this before the class and tell them you will want to discuss it. Dyslexics – and probably most non-native speakers – will be slow readers and may not get an opportunity to discuss text newly presented in class since they need to spend the time decoding it. They may have terrific contributions to make, so this is a loss all round.

Provide guided reading.

There’s also something to be said for making bibliographies focused (one chapter, half a chapter from A with the intention of examining B) and making it clear what the key texts are – and why. Find e-books where you can, and include such things as TED talks and online lectures where possible.

There is a wonderful range of apps and resources available such as dictation tools like Dragon Dictate, screen colours for visual stress, note-taking apps for lectures, support for presentations and mind mapping tools for planning. A full list of recommended resources and their uses can be found on the Diversity and Ability (DnA) site. DnA is as good as it gets, and the support you can give all your students from here is profound.

You might also like:

- British Dyslexia Association Style Guide 2022

- McNaught, A. (2012) Ten things I wish my dyslexia tutor had told me. Patoss Bulletin, Summer 2012, pp. 42-4

- Diversity and Ability – a great site packed with information and advice for supporting learning

- IvyPanda (blog) How to study with dyslexia – a comprehensive guide.

- Dyslexia and the workplace: How to thrive as an adult with dyslexia. From the Online Speech and Pathology Programmes blog.

Thank you to:

- Ray Martin for help with researching and producing this article.

- The Home School Volunteers team for providing additional resources.

- Jamie Street on Unsplash for a fabulous photo!

Want to learn more about how to design for neurodiversity?

We’re learning design nerds, and we love finding new ways to support learners.

We share all our findings in our fortnightly newsletter. Check out the examples below, and if you like them… why not sign up?

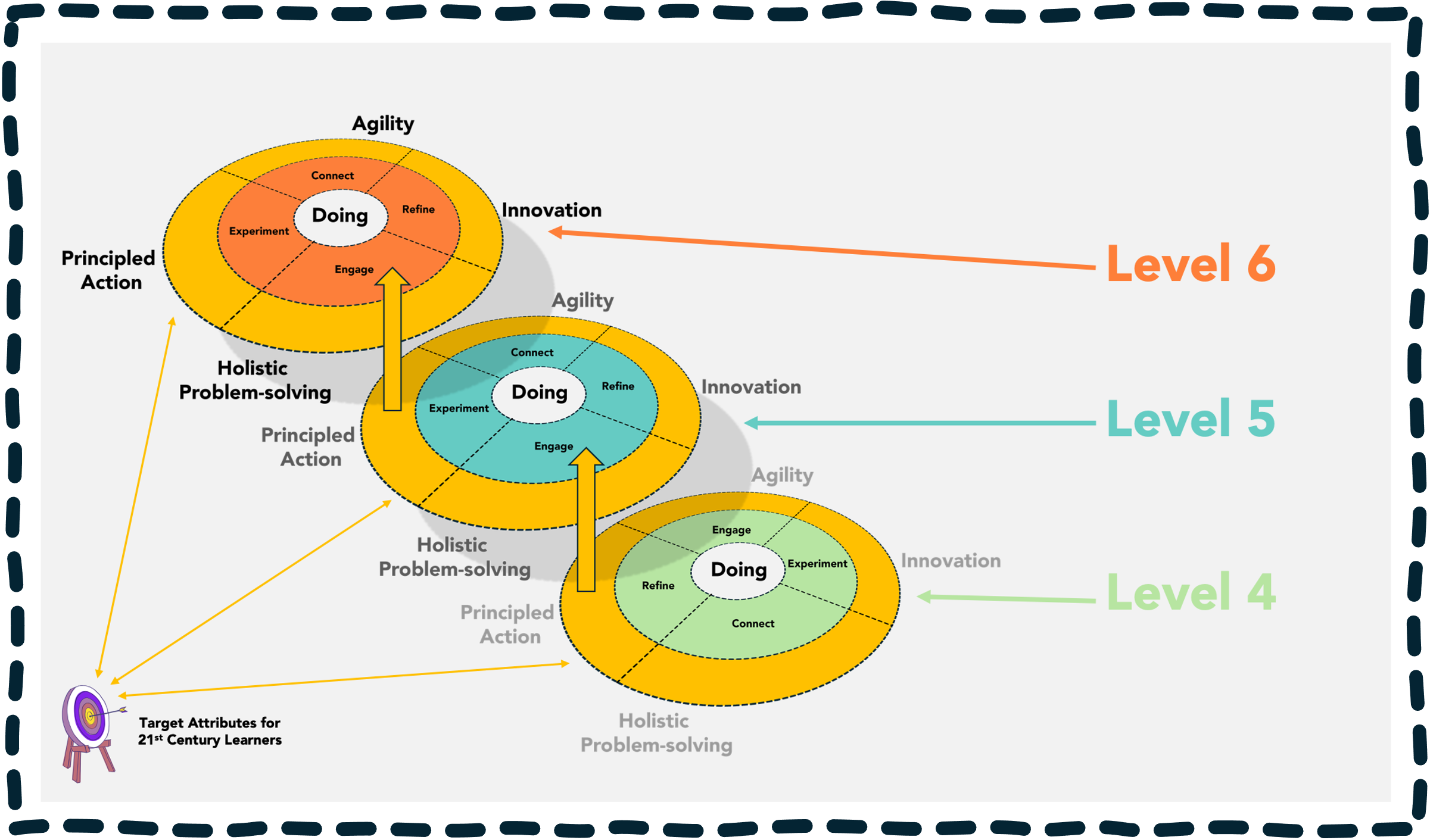

Brave New Worlds: The future of teaching excellence is now

Why improvisation sets the stage for 21st Century learning

Trackbacks/Pingbacks