‘Most learners have a wealth of experience to draw on, which, however much lip-service is paid to it, tends to get sadly neglected even in the most carefully designed learning programmes. This is of course particularly true of adult learning programmes of all kinds, including staff development.’ (Elizabeth Simpson, Foreword)

Learning by doing

Learning theories are some of the most powerful tools a learning designer can use to build learning experiences, no question. And if, like John Holt, you believe, ‘We learn to do something by doing it’, and that ‘there is no other way’, then Experiential Learning may be the tool for you.

Gibbs’ book Learning by Doing will offer you valuable insights and case studies on which to hone your learning design skills. It’s a very fine go-to book, and more of a resource rather than a read-it-through book. According to Rhona Sharpe in her 2013 preface, it’s ‘a hugely influential text in education.’

But where did Gibbs get his ideas from? And what is experiential learning anyway? Let’s take a closer look.

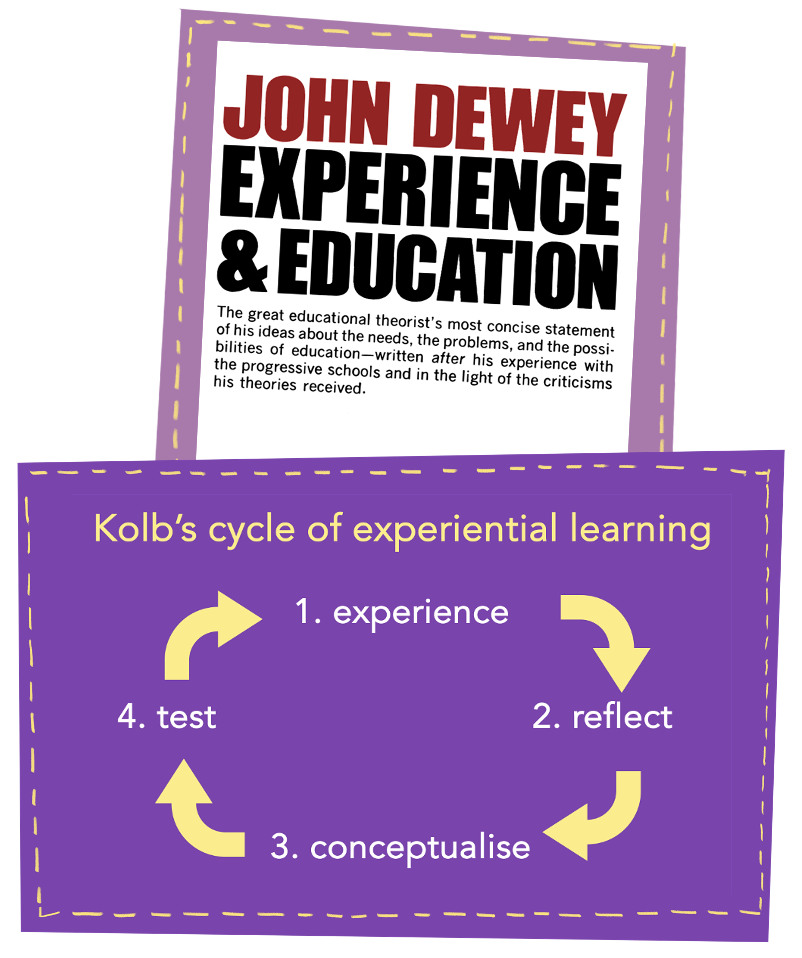

John Dewey, David Kolb and experiential learning

The theory of Experiential Learning grew out of the work of the great John Dewey (1859-1952), who saw that education paid no attention to the experience children brought to the classroom: instead, the teacher’s job was to fill the little vessels with predetermined knowledge. Dewey’s Experience and Education (1938) came out of this insight and advocated building lessons on children’s experience, not on facts.

The book has had a massive influence on the development of teaching, and on David Kolb in particular, Building on Dewey’s work, David Kolb brought two big ideas to Experiential Learning: his ‘learning styles’ inventory and his experiential learning cycle.

Kolb’s four-stage learning cycle – concrete learning, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation – has had a huge impact on teaching and training, and on how we design active learning experiences.

What does Gibbs’ cycle add?

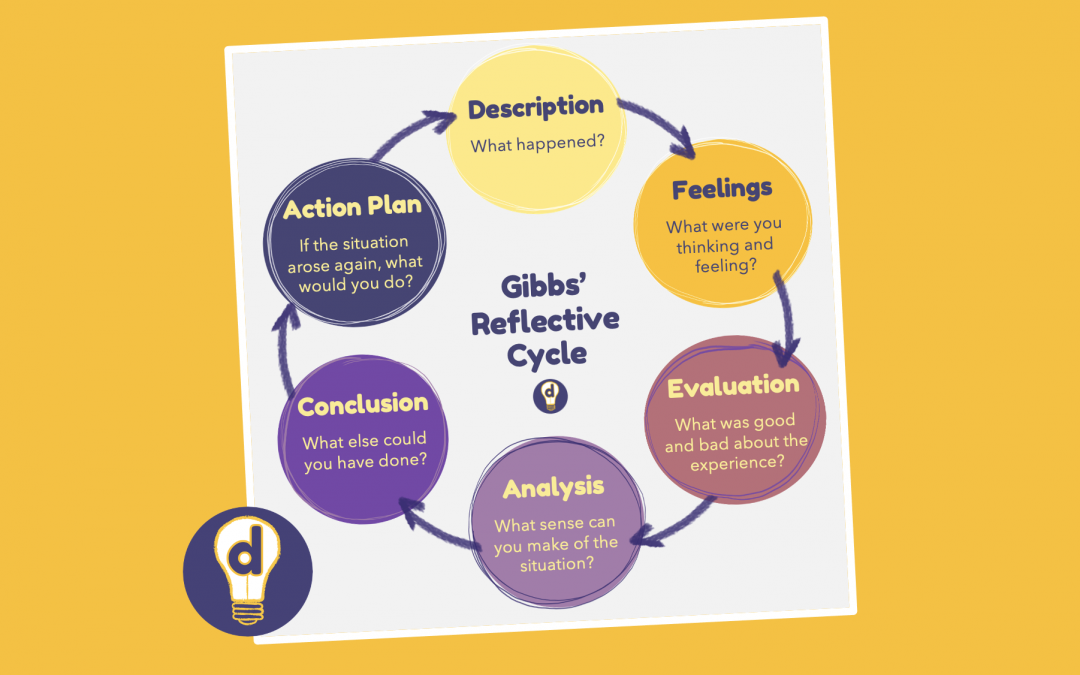

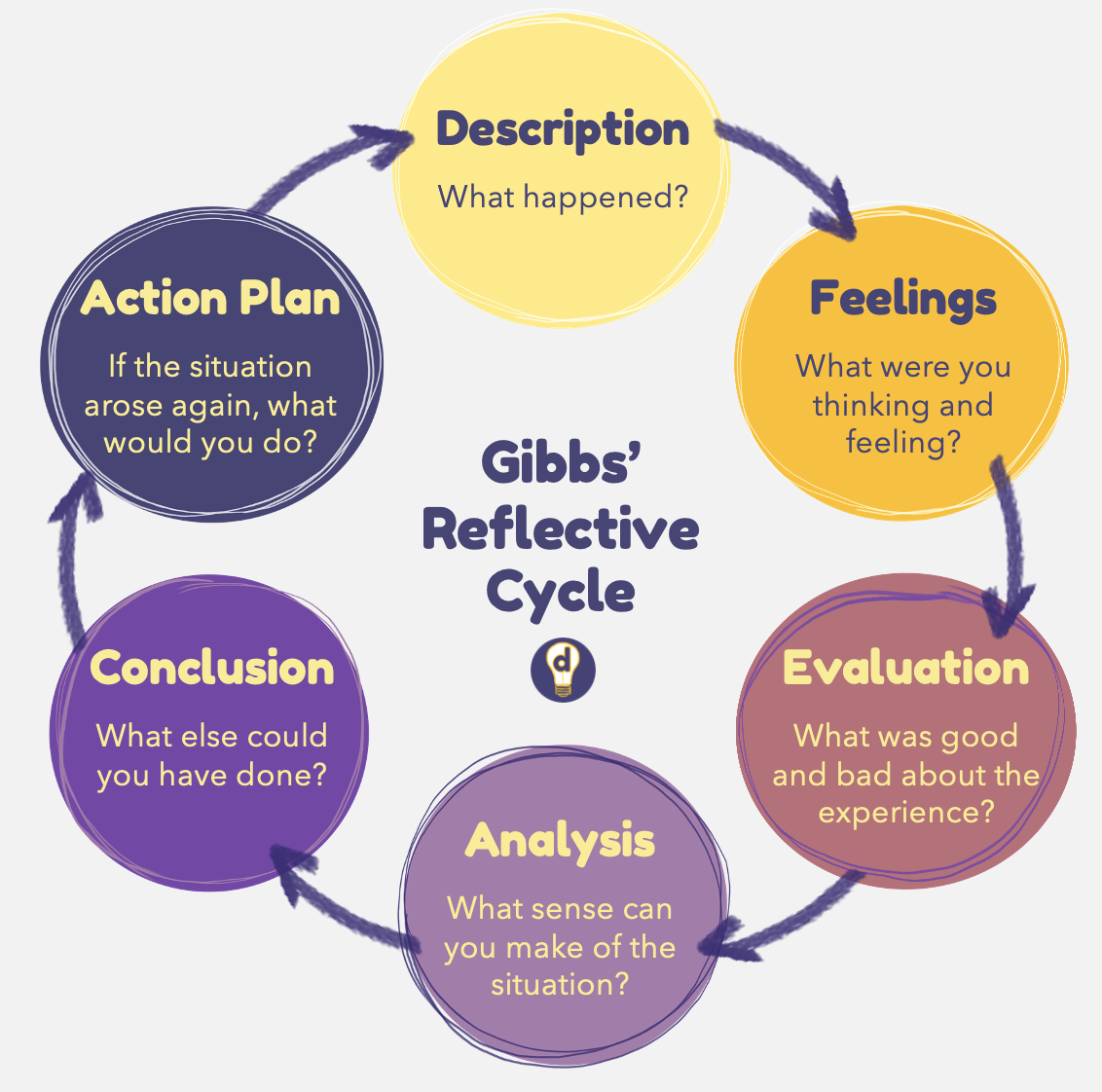

Gibbs took Kolb’s cycle and expanded into: describing, feeling, evaluating, analysing, concluding, action planning. It has, says Sharpe (2013), ‘been widely adopted by those studying, practising and teaching the skills of critical reflection.

There’s a clear explanation of how the cycle works based on examples. And the overview of what experiential learning theory does and does not cover might well be on everyone’s pinboard as an aide memoire (though why it is called ‘experimental’ learning theory here is not clear at all – a huge typo?)

You might want to give Chapter 3 a miss since it discusses learning styles – the part of this book that shows its age: the excitement of Kolb’s learning style categories (rather than individual styles) died down some years ago now. On the other hand, you may find Kolb’s inventory valuable regardless.

Chapter 4 covers practical methods for setting up and running good experiential learning sessions – can there be any aspect that has been missed? I doubt it (though I suspect that, in the 2020s, theorists would suggest more thorough, possibly different, work on group dynamics and the kinds of project with which groups might engage).

_

Tips for understanding an experience

Gibbs provides helpful advice about how students might improve their awareness/understanding of an experience. He suggests listening exercises (and an analysis of good and bad listening), logbooks, diaries, video/audio records, and structured discussions to help with understanding, reflection and memory. Tracy Harrington Atkinson’s breakdown of the Gibbs reflective cycle offers useful additions here along with useful reflective questions for every phase.

However, according to researcher Rayya Ghul, Gibbs himself was apparently puzzled as to how such a ‘coarse tool’ as Kolb’s cycle became so popular. Ghul herself ‘remain[s] unconvinced that it produces genuinely rich reflection’ (2022).

Ways to use Gibbs in learning design

Ding is a great supporter of Gibbs’ cycle of experiential learning. It provides an effective way to structure a learning experience, and can provide a different approach to reflection if you, or your learners, find Kolb’s cycle too simplistic. Here are a few tips for using Gibbs’ cycle in learning design:

Create structured reflection activities

Incorporate specific activities that prompt learners to engage with each stage of Gibbs’ cycle. For example, after a hands-on activity or simulation, provide prompts that encourage learners to describe what they did, express their feelings and initial reactions, evaluate the experience, analyze what worked well and what could be improved, draw conclusions, and plan actions for future applications. These structured reflection activities can be integrated into e-learning modules, classroom discussions, or self-paced exercises.

Provide multimodal learning resources

Provide diverse resources that cater to different learning preferences and styles. This could include written reflections, audio or video recordings, visual aids, and interactive simulations. By offering a variety of resources, you accommodate various learning styles and preferences, ensuring that learners have the tools they need to engage with each stage of the cycle effectively.

Enable peer feedback and Interaction

Foster a learning environment that encourages peer feedback and interaction. This can be achieved through activities such as group discussions, peer reviews, or collaborative projects. Encourage learners to share their reflections and insights with each other, providing opportunities for constructive feedback. This not only reinforces the learning process but also promotes a sense of community and shared understanding among learners.

You might also like:

-

Ghul, R. (2022) Using an “orientation to reflection” framework. Learning & Teaching Enhancement Series: Reflective Learning.

-

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. Further Education Unit, Oxford Polytechnic.

-

Harrington Atkinson, T. (2023) Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle. Paving the Way.

-

Wellington, B. & Austin, P. (1996) Orientations to reflective practice. Educational Research. 38(3), 307–316.

Thank you to:

- Ray Martin for her help with researching and preparing this article

Want to learn how to build great courses?

We run a PGCert, PGDip and MA in Creative Teaching and Learning Design.

Find out which stage is right for you.