In one of our Friday chats, Phil and I recently explored the Kuleshov Effect and its implications for learning design. While Phil is something of a film buff, I’m definitely not – so I spent some time researching this concept prior to the discussion to ensure I knew what he was talking about. And it turns out that the Kuleshov Effect can tell us a lot about the work that learning designers do.

The learning designer as ‘editor’

The Kuleshov Effect focuses on the power of a film editor to influence the meaning that an audience experiences. But before we get into that, I want to take a moment to compare the role of a film editor with that of a learning designer.

For a long time, Phil and I have grappled with the difficult of explaining learning design to people. But viewing the learning designer as an editor is a helpful analogy to describe the work we do. Editors are responsible for making sense of a film director’s vision of what the film should be, and this often involves ‘editing’ out footage that the director would otherwise leave in.

This analogy produces a useful comparison between the learning-designer-as-editor and the subject-matter-expert-as-director. Whereas a SME is responsible for delivering a selection of high quality content, the learning designer’s role is to edit the content to ensure the curriculum doesn’t become overly stuffed with content.

The power of gaps in sequencing

Now let’s bring in Kuleshov. Lev Kuleshov was a Russian editor who believed that the acting in a film was less important that how the film was edited. Kuleshov argued that an editor can fundamentally change the meaning an audience experiences by changing the order in which shots are presented. To use his words: “more meaning is created by the interaction of two shots than by any shot in isolation”.

This has huge implications for learning design, because it demonstrates the importance of leaving space for learning to occur. If there is too much instruction going on, the learner quickly becomes passive. But by leaving ‘productive gaps’ in the sequencing, learners engage their imagination as they work to make connections between activities or moments of interaction.

If we apply the Kuleshov Effect to learning design, it enables us to reduce the amount of instruction required. Just as an editor understands the end-to-end narrative of a film, the learning designer’s role is to understand the end-to-end learning experience. In both cases, the job involves providing just enough information to ensure the audience understands what’s going on, and leaving enough gaps to engage their imagination.

How juxtaposing experiences develops employability skills

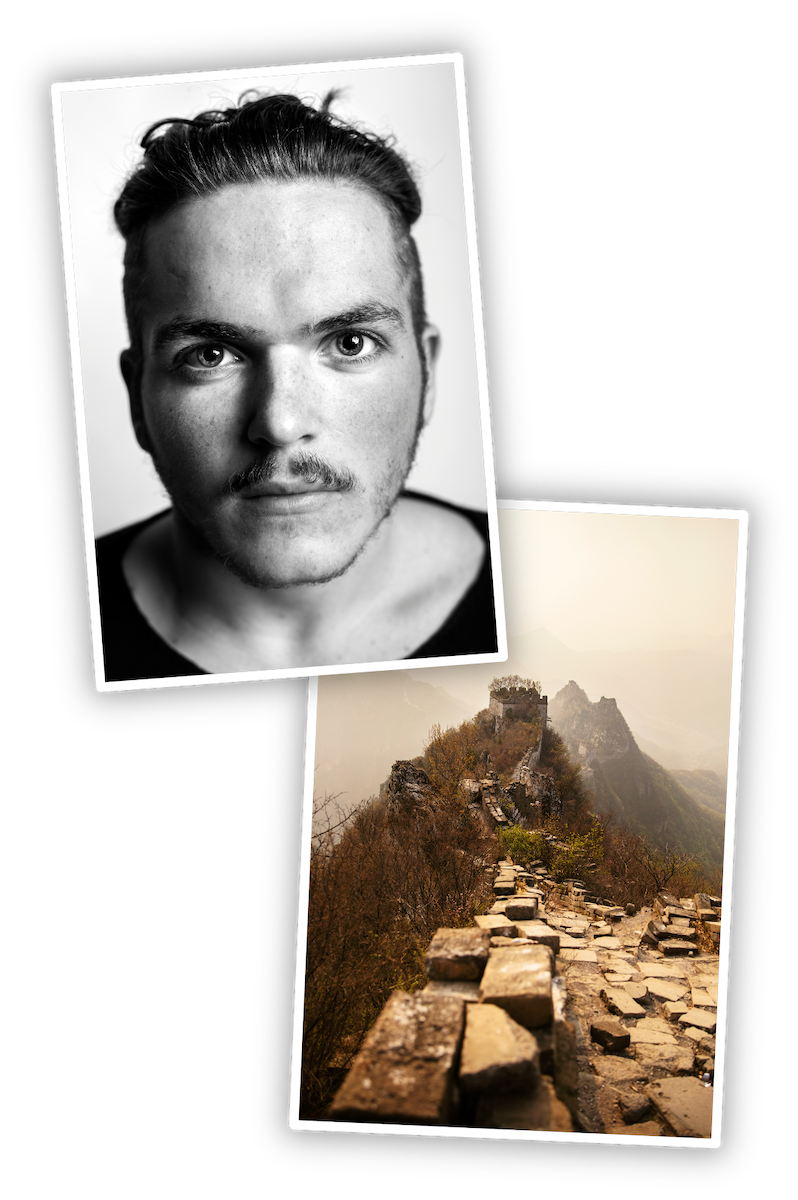

At the heart of the Kuleshov Effect is the role of juxtaposition. In his famous experiment, he first showed an expressionless face (the first ‘shot’) and then placed a contrasting second shot after it By changing the second shot, he demonstrated that meaning emerges in the viewer’s mind rather than from the footage itself.

This offers a useful way to think about how skills development actually works in practice. University education often treats skills as fixed endpoints – as if once you’ve learned to do something, that skill exists in isolation as a complete thing. But just as Kuleshov showed that a neutral face takes on different meanings when juxtaposed with different images, skills take on different qualities and applications when juxtaposed with different real-world contexts and problems.

This suggests something profound about the nature of skills development. When a student learns a technical skill – whether that’s data analysis, architectural design, or photography – that skill in isolation is essentially neutral. It’s like Kuleshov’s expressionless face: it contains potential but not inherent meaning. The real meaning and value of the skill emerges only through its juxtaposition with real-world problems and scenarios that test and transform it. This is why employers often say that technical skills alone aren’t enough – they need graduates who can adapt and apply those skills in unpredictable situations.

This should fundamentally change how we think about curriculum design. Rather than treating skills development as a linear process of acquisition, we should be creating deliberate juxtapositions between skills and scenarios throughout the learning journey. This might mean exposing students to the same skill in three very different contexts in quick succession, helping them understand that skills aren’t fixed points but rather starting points for problem-solving.

Using ambiguity to increase learning

The value of producing deliberate ambiguity in curriculum design is also supported by research. In 2019, a longitudinal study by Sinha and Kapur tested the difference between teaching first or experiencing a problem first. In the research, students who were required to tackle a problem before receiving any instruction showed a learning gain of around 20% compared with those who received instruction before tackling the problem.

This tells us that we ignore gaps at our peril. As learning designers, we should create and sequence activities that engage learners’ problem-solving skills and enable them to create their own meaning before we teach into the space. This is a skilful act of design, as learners need to feel sufficiently ‘held’ and supported to have the confidence to deal with ambiguity.

Meaningful learning lies in the edit

In film, the editor shapes meaning through careful selection and sequencing, often making difficult decisions about what to remove. Similarly, learning designers shape the learning journey through careful curation and sequencing of experiences.

The learning designer, like the editor, brings a strategic perspective – understanding that what matters is not the individual pieces of content, but how they work together to create meaning in the learner’s mind. Like film editors, we operate from a position that is “subject-adjacent” rather than deeply embedded in the subject matter. This gives us a unique perspective – we can see the whole journey and make strategic decisions about what to include, what to remove, and how to sequence experiences for maximum impact.

This makes the learning designer’s role highly strategic. We’re not just creating content – we’re curating experiences that create the conditions for learning to emerge.

Want to learn how to build great courses?

We run a PGCert, PGDip and MA in Creative Teaching and Learning Design.

Find out which stage is right for you.